Insect identifications

INSECT IDENTIFICATIONS

I get a lot of requests for identification of insects from Pest Control Operators, and the general public. Many times these are sent as fuzzy, poor quality WhatsApp images taken with a cell phone camera. Some of these are then also of bugs that have been killed by whacking them. It is often very difficult to identify these.

Fig. 1. A typical WhatsApp photo requesting an identification. The only identification that can be given from such a photo is that it is a male flying ant (or maybe a wasp species?). As soon as the image is enlarged (below), it loses all resolution, and no further identification can be made.

It’s fairly easy to get better photographs from a cell phone camera. The photo below is of a maize or rice weevil (Sitophilus) that I took with my Samsung cell phone – it’s actually not a very good photo, but much better than the one illustrated above.

The photo above was taken with an inexpensive accessory for the phone that takes “macro” photographs, as illustrated below. There are many such accessories for cell phones available, some much more sophisticated and expensive than that shown here.

Fig. 2. One of my all-time favourite requests for identification. A bug squashed flat on a piece of paper and stuck down with tape. These types of “specimens” are surprisingly often sent to me.

Most of the photos I receive also do not have a scale for reference. So it’s very difficult to sometimes ascertain size of the specimen. Photographs should be taken with some familiar object in place to give an indication of size (a safety match is a good size indicator for most insects). It’s also important to include as much information about the specimen as possible to enable an accurate identification to be made – i.e. where found, what was the behaviour, storage conditions etc.

There are approximately 1,5 million named species of insects (Costello et al., 2013), so you can imagine it is not easy to identify insects to species level, especially when all one gets is photos and specimens as illustrated above. In addition it is estimated that there are at least another 8 million species that are not described (Stork et al., 2015). An estimate of southern African species in 1995 was 44 000 species, although there remain many more species that are unknown, especially is some groups of insects (Scholtz and Chown, 1995). Another recent estimate of insect species in South Africa put the total at 250,000 (Picker et al., 2019).

If Pest Control Professionals want to purchase books that can assist them in identifying insects I would recommend the following as a good set of books to use (Dippenaar-Schoeman, 2014, Picker et al., 2019, Scholtz et al., 2021, Slingsby, 2017, Woodhall, 2020).

All of these can be purchased online (I’m not sure the ant book is still available). Here are the links to do this:

https://lapa.co.za/catalogsearch/result/?q=spiders

https://slingsby-maps.myshopify.com/search?q=ants+southern+africa

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.co.za/search/books?query=insects

The Pollinators, Predators and Parasites book is particularly interesting reading about all the different groups of insects in South Africa and their behaviour and ecology.

The other interesting fact about all the requests I get for identification is the question: “How do I get rid of/kill them”. While I can understand and the request when it comes from a PCO, (because it is a potential job for them), I do not understand why people in general want to get rid of insects. Often the insects in question are beneficial or completely harmless. Why then kill them? Many PCOs when I question this state that the customer wants the insect gone, never mind what it is. It reminds me of a case I had years ago when a member of the public contacted me in Johannesburg. He stayed in an up-market house in a gated complex, and he had a monthly contract with a pest control company. The PCO company would routinely spray all skirtings in the house with deltamethrin, and all perimeters outside with chlorpyrifos – ROUTINELY. When I asked the owner why he was doing this, he said his wife couldn’t stand the sight of any “gogga”. And he was carrying on with the contract even although his small daughter had ended up in hospital due to organophosphate poisoning.

Without going into any philosophical musings, why is it that people are so removed from nature that they cannot tolerate any insects in their environment? And some blame for this can be laid at the door of the PCO, because they do not (or cannot) explain the behaviour and biology of the insects to the customers, and their focus is only on doing a treatment so that they can invoice.

And not to mention the many pundits who cheerfully identify insects from pictures they have seen on the internet. In many such cases the photos and info they access is related to North American or European insects. They will blissfully identify pictures from WhatsApp photos and mention insects (scientific names and all) that are only found in the USA – best recent example was a spider identification from the Eastern Cape identified as a spider only found in Madagascar. Obviously none of this is real “fake news”, but trust me the internet is not a reliable way to identify insects – I wish people would stop doing that.

To get a proper identification you need to consult an expert – in this case an entomologist. There are not that many of us around, and no entomologist can identify all species, especially not to species level, given that there are so many extant species, with many remaining undescribed. And consulting an entomologist does not mean sending a fuzzy WhatsApp picture. For positive identification one needs to see the physical specimen. And often one would need to examine it under a microscope as illustrated below from my office.

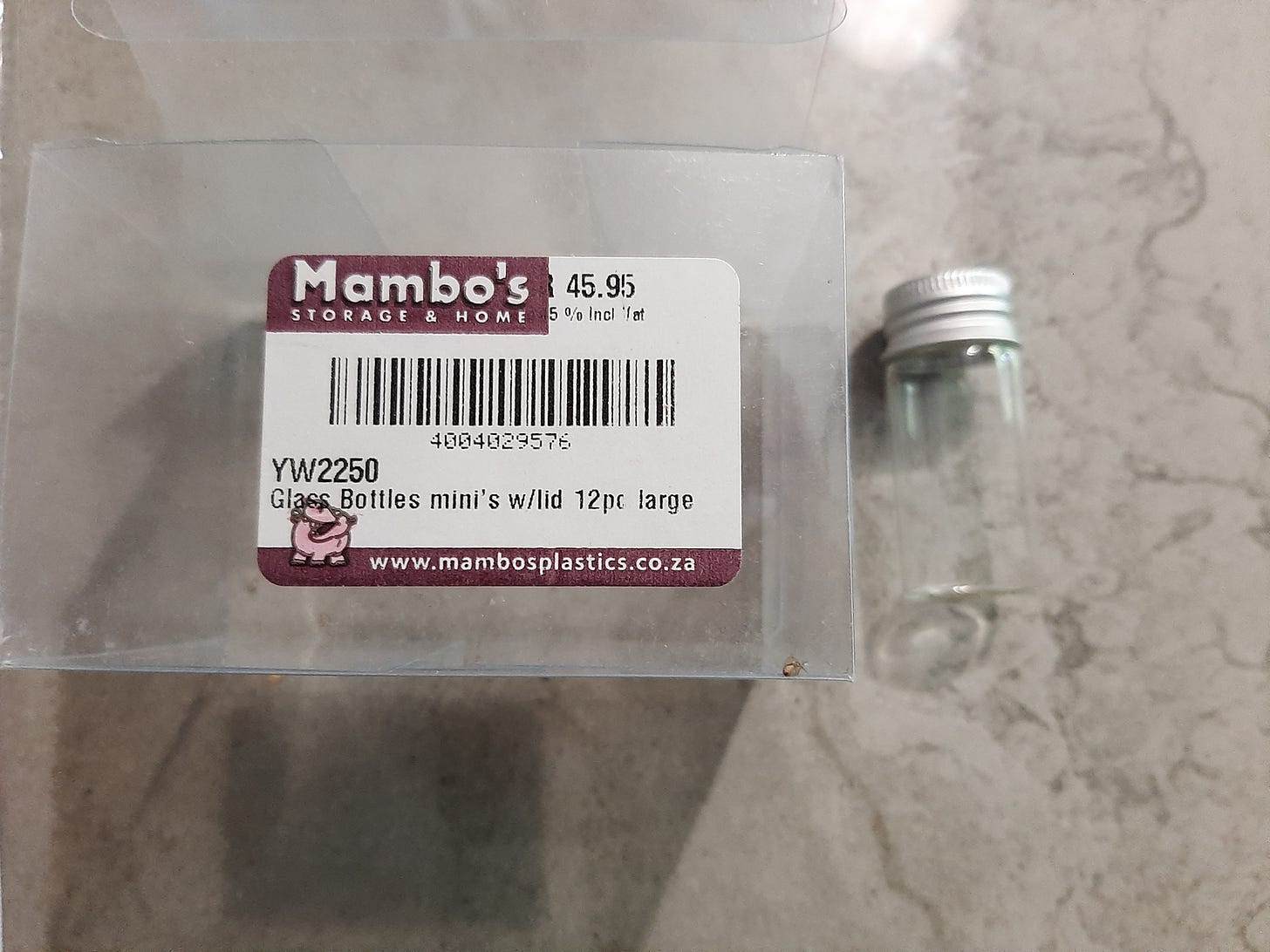

Many of the specimens I receive for identification are Stored Product Insects (SPIs). In various food safety scenarios it is important to have accurate identification of the SPI involved. Unfortunately many times the specimens are send still in the affected commodity or product, and by the time it gets to my lab, the product/commodity is sometimes rotten (vrot), or the SPI has long ago exited the packaging. Many SPIs are also capable of penetrating various packaging types, thus escaping. It makes much more sense to preserve the specimen separately so that it can be positively identified. And it’s easy to do this – the photo below shows a small bottle purchased form my local packaging supplier. These are cheap and should be readily available. They also seal quite well.

And what should one use as a preservative? After Covid-19 almost all of us should have some sort of sanitizer lying around. These sanitizers are mostly high percentage alcohol solutions, and are thus OK to preserve insect specimens. Use the liquid types, not the gel type of sanitizer.

If any PCOs want to get some entomological supplies there is a South African website where you can order some things that will make your life easier when catching and preserving insects:

https://madhornet.co.za/

References

COSTELLO, M. J., MAY RM FAU - STORK, N. E. & STORK, N. E. 2013. Can we name Earth's species before they go extinct? Science, Jan 25;339(6118):413-6.

DIPPENAAR-SCHOEMAN, A. 2014. Field guide to the spiders of South Africa, Pretoria, Lapa Publishers.

PICKER, M., GRIFFITHS, C. & WEAVING, A. 2019. Field guide to insects of South Africa. 3rd Edition, Century City, Struik Nature.

SCHOLTZ, C., SCHOLTZ, J. & DE KLERK, H. 2021. Pollinators Predators & Parasites. The ecological roles of insects in southern Africa, Century City, Struik Nature.

SCHOLTZ, C. H. & CHOWN, S. L. 1995. Insects in Southern Africa: How many species are there? South African Journal of Science, 91, 124-126.

SLINGSBY, P. 2017. Ants of southern Africa, Muizenberg, Slingsby Maps.

STORK, N. E., MCBROOM, J., GELY, C. & HAMILTON, A. J. 2015. New approaches narrow global species estimates for beetles, insects, and terrestrial arthropods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 7519-7523.

WOODHALL, S. 2020. Field guide to butterflies of South Africa. 2nd Edition, Century City, Struik Nature.